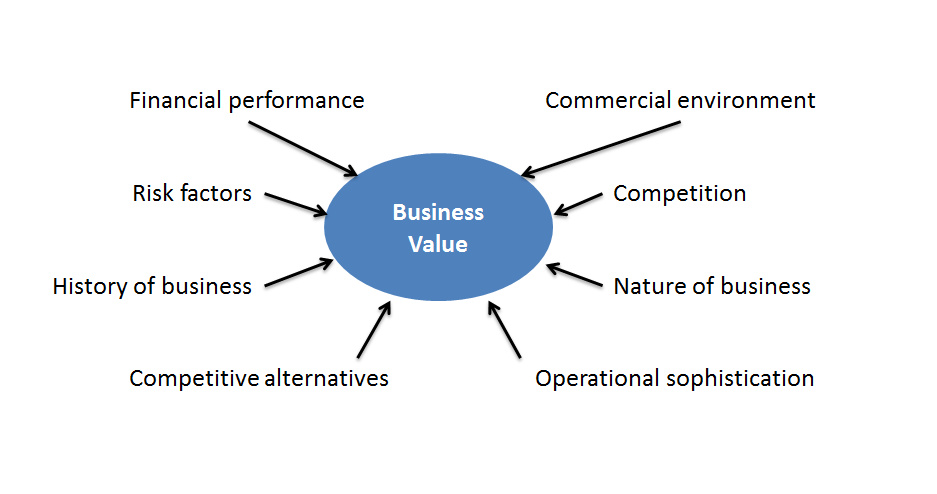

Business valuation methods vary and are used to determine a value that represents the price that a business can be sold for at a particular time. No method is precise.

Your business is likely to be your largest asset, so it’s natural to want to know what it is worth. The problem is: business valuation is not an exact science. It has a purely financial component that can be calculated. It also has a subjective side where the value perceived by each potential buyer varies with each buyer’s circumstances.

The price that will be finally achieved is only what a buyer is willing to pay. This may be a lot less that the value the seller has calculated.

This article covers the most common business valuation methods. These methods are true for smaller business as opposed strategic sales, where a business’s value is based on what it would be worth in the acquirer’s hands.

Income based business valuation

Earnings Multiple: The most commonly used business valuation method is the Earnings Multiple or (Price/Earnings ratio) method. As the name suggests, the value of the business is quoted as a multiple of its future maintainable income. The earnings multiples vary for businesses of different size within the same industry and between industries for businesses of the same size. One arrives at a business valuation by looking at comparable business sale multiples and applying them to the business under consideration.

Discounted Cash Flow: The discounted cash flow method looks at the forecasted cash flows and then applies a discount rate to bring them back to a value in terms of today’s dollars. The discount rate used increases with the level of risk, possible forecast variances, and the length of time over which the cash flows occur.

Essentially the drivers of value when you use this method are

• how much profit your business is expected to make in the future

• how reliable those estimates are.

Assets-based

This method considers the value of a business’s hard assets minus its liabilities or debts owed. One uses the net asset value to value the business as if were to be closed down and no longer be able to generate any profits.

This business valuation method often produces the lowest value because it takes no account of ‘goodwill’. Goodwill is defined as the difference between a company’s market value (what someone is willing to pay for it) and the value of the net assets as described above. Goodwill should take into account all of the intangible value aspects of the business, such as: its earnings potential; reputation; and the ongoing relationships with customers and suppliers. Coming up with a valid sum for goodwill then becomes the issue.

Market based

The market based approach looks at businesses that operate in the same industries. If there are sufficient examples of sales available, then a common rule-of-thumb valuation method can be applied, such as an earnings multiple.

Other examples are:

• “x” times book value – of relevance for real estate management companies

• “y” times EBIT – Earnings before Interest and Tax – applies for most businesses

• “z” times EBITDA for businesses who have high capital costs, and so are assessed before depreciation or amortisation are taken into account.

Size of a business plays a big part in determining the relative value of businesses in similar or comparable industries. Typically, it is the larger, often publicly listed business whose sales price becomes public knowledge. Compared to those, most smaller business sales are concluded at much lower relative valuations. Anyone contemplating a sale should bare this in mind.

The difference between a vendor’s and a purchaser’s business valuation

Every time a business goes on the market, the owners either have the business formally valued or come up with a notional value of their own. This then becomes the asking price.

Purchasers on the other hand may use any one or more of the methods described above to arrive at what the value of the business is to them. Needless to say, these numbers are usually quite different. The difference is usually settled by negotiation. The seller invariably has to discount his asking price.

Strategic purchases

Sometimes a business is acquired for very strategic reasons, such as patent ownership, technical capability or market access. In these cases none of the business valuation methods described has any relevance.

Take for example Facebook’s $1bn acquisition of Instagram in 2012. Here there was certainly no consideration made for the earnings of Instagram – it had none. Five years later, Instagram’s 30 million user base had grown to 600 million. With what Facebook had in mind in terms of future monetisation from advertising, it was one of the shrewdest Silicon Valley acquisitions in history. A brilliant investment even at that eye-watering price.

Strategic acquisitions break all the rules and lead to business valuations that are much, much higher.

How should you approach value maximising your business?

In the first instance, you need to fully understand what valuation maximisation issues your business faces and then work out how these need to be addressed should you wish to get top value (and in fact, find a buyer!). Its best to have your business assessed by an independent and impartial 3rd party. Then you can decide on how to move forward.